Being one of the most literate and technologically advanced countries in the world, Japan is the only Asian country so far to belong to the first world. Contrary to many other developed countries, Japan still has a very homogenous population and a dominant cultural practice. According to Japanese studies, it is estimated that approximately 98% of its population is of ‘ethnic’ Japanese descent. The other 2% is suggested to consist of minorities from Korea, Brazil and the Philippines. Within a global perspective, it does raise a few questions as to how Japan has this few migrants or different ethnicities living within the country.

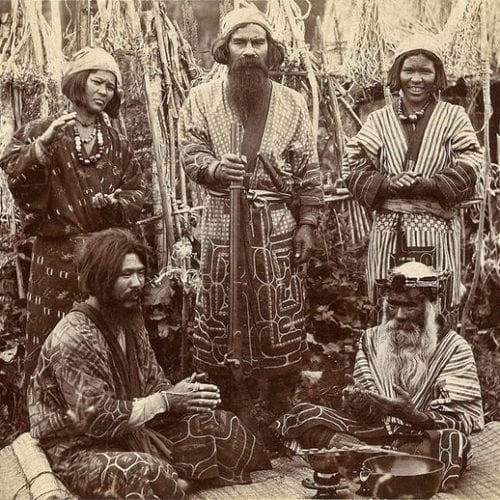

Apparently, what is often overlooked in Japanese demographic science concerning homogeneity, are 3 ‘hidden’ minorities which have been in Japan for a very long time. By far the most distinct is the indigenous Ainu from Hokkaido (the Northern Island of Japan). It is believed the Ainu have descended from the first humans to have inhabited a vast part of the Far East in prehistoric times, commonly known as the Jomon People.

The Ainu were a very prosperous community due to the natural riches of the island of Hokkaido and its biodiversity, living both off of hunting and fishing and the cultivation of small crops. Up until the 14th century, there was little to no contact between the Japanese and the people of Hokkaido, but this quickly changed as the Japanese became aware of the fertility of the Ainu lands.

At first, the Ainu performed some trade with Japan, which quickly resulted in escalations and oppression of their people. The Japanese were more advanced when it came to technological skills and invaded the Ainu lands for mining practices, flower mills and beer breweries. In 1899, the Japanese government effectively colonized Hokkaido by declaring upon the Ainu the Japanese citizenship, denying them of their language, cultural practices and their land.

Even though at the time this process was openly referred to as ‘the colonization of Hokkaido’, current elites have rephrased it by using the word ‘kaitaku’, which conveys a sense of opening up or reclaiming the Ainu Islands, whereas the lands had previously always belonged to the indigenous of Hokkaido and not to the Japanese.

The assimilation of the Ainu by Japan went surprisingly fast. A century later the population had halved and only 25.000 ‘official’ Ainu remain in Hokkaido today. However, it is believed there are about 175.000 more with the same ancestry all over the country, these are people who have consciously or unconsciously denied their background or simply lack knowledge about their indigenous heritage by means of assimilation. This is probably because back at the beginning of the 20th century, many Ainu encouraged their offspring to marry Japanese men out of fear of marginalization and poverty.

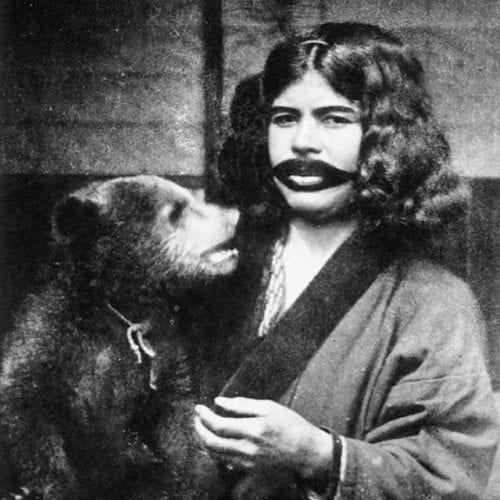

The indigenous have therefore largely lost their distinct ethnic features. Ainu people originally tend to have light skin, a stout frame, deep-set eyes with what could be considered a European shape, and relatively a lot of thick, wavy hair. Full-blooded Ainu may have even had blue eyes with brown hair.

The above may demonstrate the demographic politics of Japan in emphasizing its cultural uniqueness through this idea of homogeneity, whereby marginalizing ethnic minorities and multiculturalism, ignoring the rise of a global community.

In recent years, foreign scholars have encouraged the Japanese elite to re-invent the status quo towards a more inclusive one. Some even say that ‘the myth of Japanese homogeneity’ is responsible for sending Japan down a spiral of crushing debt and an ageing workforce, unable to keep up with a modernized and diverse economy. The Ainu people seem to be on the forefront of this movement towards a new paradigm, advocating for a more balanced lifestyle in- and outside of Japan.

On June 6, 2008, the Japanese House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution calling upon the government to recognize the Ainu people as indigenous to Japan and urging an end to discrimination against the group. The resolution recognised the Ainu people as an indigenous people with a distinct language, religion and culture. The government immediately followed with a statement acknowledging its recognition, stating, “The government would like to solemnly accept the historical fact that many Ainu were discriminated against and forced into poverty with the advancement of modernization, despite being legally equal to (Japanese) people”.

Japan’s plan to host the United Nations’ Climate Summit in Hokkaido during July of that same year and much-anticipated global attention were probably the primary factors in the hasty adoption of the resolution. As such, the G8 Summit made possible a critical moment, whereby a new generation of grassroots Ainu leaders are enabled to launch new initiatives and reclaim their identity.

Want to read more on the social structures behind Japanese homogeneity? Go here.

Want to read more on the G8 Summit in Hokkaido and its resolution for the Ainu people? Go here.