In the 1980s, native American artists such as Carl Beam, Jeff Thomas, Bob Boyer, Robert Houle, Gerald McMaster, Edward Poitras, Shelley Niro, James Luna and Pierre Sioui (amongst others) were true provocateurs. They declared that the lack of indigenous art in major art institutions across Northern America was intrinsically connected to an ongoing indifference towards and exclusion of indigenous people from dominant culture. These artists were among the first who weren’t afraid to address the issue and created, often humorous, powerful and provocative works of art. In place of inaccurate and stereotypical images of indigenous peoples, they used a visual language which asserted their communities’ rights to self-determination, self-representation and sovereignty.

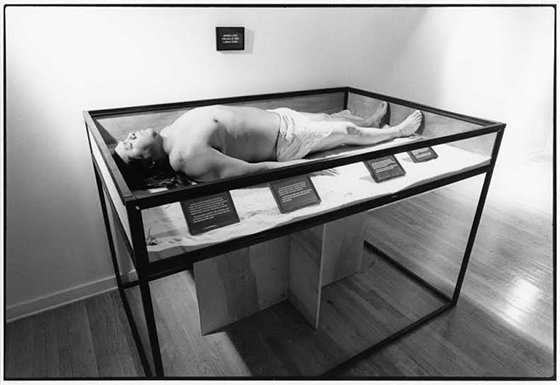

‘Artifact Piece’ by artist James Luna (1987)

Beyond 1980’s indigenous art being a tool for decolonization, it was also a way to re-think our position in the world and the way we perceive it. The above image depicts a performance piece by artist James Luna. In this performance, Luna “installed’ himself in an exhibition case in the San Diego Museum of Man in a section on the Kumeyaay Indians, who once inhabited San Diego County. Along with the installation came a few displays pointing out scars on his body and aiming to describe Luna’s full array of interests in just a few sentences: “from beat literature to indian music, country and western, old school, pop and rock, new stuff—I listen to it all.” The work revealed not only the colonial gaze, but also the absurdity of its mission to represent whole cultures through a few well-chosen artifacts.

With ‘Artifact Piece’, Luna tried to make clear that we are all human beings, whether native or not: “I’m a Native man, born in 1950, who wasn’t born into a tepee, but who was raised in front of a TV. I’m a man who went to college …I want to speak to … everyone who was also born in front of a TV. I want to speak to you as a whole person, and to bring along my cultural side as well.”

Ultimately, it’s the work of indigenous artists like Luna’s Artifact Piece that created a widespread notion of the status quo concerning cultural survival and revival, concern of the land, the institutionalization of arts, representation and cultural appropriation, the place of women within society and identity. How they did it? By disrupting assumed certainties. Art is a very powerful tool to question what’s comfortable, especially when it comes to Western superiority and the inferiority of indigenous people. To decolonize the arts meant to embrace a common future, together.

Nowadays, it’s influential indigenous artists such as Nicholas Galanin, Merrit Johnson, Steven Paul Judd, Jeffrey Gibson or Richard Bell who challenge topics such as cultural appropriation and climate change and put themselves forward as both artists and activists. In an interview with Hyperallergic artmagazine last November, Galanin said ‘we are ready to fight back.’ Being a Tlingit-Unangax̂ artist from Alaska, Galanin addresses climate change and its connections to white supremacy.

Everything We’ve Ever Been, Everything We Are Right Now is the ambitious title to Galanins’ solo- exhibition at Macalester College’s Law Warschaw Gallery. Two polar bears, on opposite sides of a central wall, frame the exhibition. “We Dreamt Deaf” (2015) is a taxidermic bear that was shot by a white hunter in Shishmaref, Alaska, before Galanin was born. Located on an island off the coast of Alaska, Shishmaref is sinking into the sea, making subsistence hunting and fishing dangerous and nearly impossible for the indigenous community based there. Part bear, part rug, Galanin tells Hyperallergic that the piece refers to the dangers of ignoring climate change, but it’s also about amnesia. The polar bear’s state illustrates the consequences of humans forgetting their place in the world, where energy extraction comes at the cost of animals, cultures, and entire ecosystems.

‘We Dreamt Deaf’ by Nicholas Galanin (2017), photo courtesy of Hyperallergic Magazine

Climate change concerns all of us and contemporary artists from all over the world are visualizing the effects of global warming in their art. However, it seems that indigenous people and artists alike are the best spokespersons for the natural world and rapidly declining ecosystems, after all they are the ones who already had to deal with a past in which they lost so much of their habitat that the future remains uncertain till this day. Now, with entire species of flora and fauna disappearing all over the world, dominant culture is faced with the realities of a similar fate. The ways in which indigenous artists translate the issues of our times into visual artworks speaks volumes about their history with inequality, as what has caused global warming is the exact same as what has caused the demise of their cultures: colonization.

Anyone who denies that there is a correlation between climate change and colonization, aka the extraction of resources, might say that we don’t need climate justice movements such as the one Nicholas Galanin is referring to when he says ‘we are ready to fight back.’ More and more often, indigenous artists and musicians use their disciplines as a means for change, calling themselves ‘warriors’ as they fearlessly enter the public arena. They have done this before, they know what it takes to be a warrior, and not the kind that is dominantly perceived as a pawn within someone else’s war schemes. According to native American traditions, a warrior is something different. As Lakota Chief Sitting Bull said:

The warrior, for us, is one who sacrifices himself for the good of others. His task is to take care of the elderly, the defenseless, those who cannot provide for themselves, and above all, the children – the future of humanity.

It’s safe to say that indigenous artists are among some of the most revolutionary and interesting contemporaries working at the cutting edge of activism and art, fearlessly willing to use their body as a political and creative tool for justice. But a quick search into the dominant art industry’s favorites teaches us that none of those mentioned are in fact indigenous. A 2018 article in the New York Times shortlists 12 artists on Climate Change, called ‘A dozen artistic responses to one of the greatest threats of our time.’ Again, there is no place for indigenous voices there.

Many scholars write about indigenous art, referring to their powerful expressions and means to re-shape our thinking about native culture, but hardly anyone dares to compare it to non-indigenous secular contemporary art. Indigenous art is always judged for its quality within a separate category, and this colonial framework is exactly what James Luna tried to challenge in ‘Artifact Piece’.

- Cover photo courtesy: ‘Two Loves’ (2015) by Steven Paul Judd.