A common denominator for many indigenous cultures is the worship of the Sun god or goddess, called Ra in ancient Egypt, Huitzilopochtli to the Aztecs or Beiwe to the Saami. Each has and had its own story relating the significance of the sun for the evolution of their civilization and each has its own rituals revolving around the bringer of light and new life. With the Winter Solstice right behind us (occurring anywhere between the 19th and 22nd of december in the Northern Hemisphere, depending on your location), most cultures celebrate the current re-birth of the sun to create new life in the course of the next half year, reaching its peak at the Summer Solstice (21st of june in the Northern Hemisphere).

Not unlike many of these ancient cultures, the Maori people of New Zealand have created a ritualistic dance in celebration of light triumphing over darkness, the Kapa Haka. According to Maori mythology, Tane-rore, the son of the Sun god Tama- nui- te- ra, was responsible for the birth of dance. Movements used in haka are derived from Tane-rore dancing for his mother Hine- raumati. It is believed that on occasions when the land is so hot that the air shimmers, you can see Tane-rore perform, the wiriwiri or shimmering air is reminiscent of his trembling hand actions.

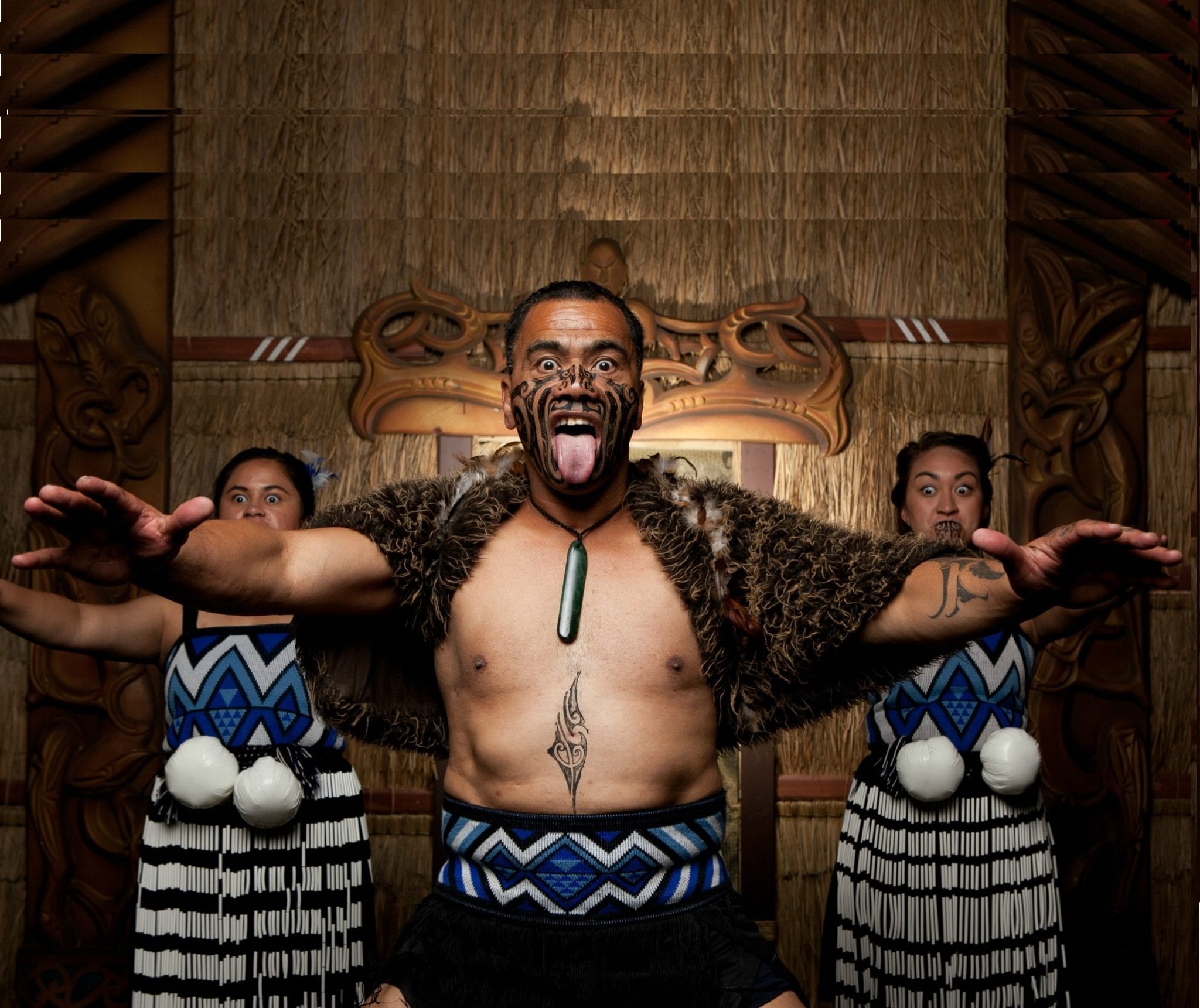

Haka was made famous by the New Zealand native rugby team, performing the dance to intimidate their opponents before matches ever since 1888. The type of Haka the All Blacks perform before battle is called “Ka mate, Ka mate”, which translates into “‘Tis death, ’tis death”. Ka mate haka was composed in 1820 by the war leader Te Rauparaha of the Ngati Toa tribe. It tells the story of him hiding for his enemies in a food-pit, only to climb out towards the light when he was met by a hairy man and chief who was friendly to him. This haka was since then used before battle to bring courage to the tribe and to emphasize the triumph of light over darkness. One should admit, the apparent fierceness of this eye-rolling, tongue flicking war dance is a very impressive display of pride, strength and tribal unity; Actions include forceful foot-stamping, tongue protrusions and rhythmic body slapping to accompany a loud chant:

Tēnei te tangata pūhuruhuru: This is the hairy man

Nāna nei i tiki mai whakawhiti te rā: Who brought the sun and caused it to shine

Ā, upane! ka upane!: A step upward, another step upward!

Ā, upane, ka upane, whiti te ra: A step upward, another… the Sun shines!

However, many have accused the Ka Mate Haka made famous by the All Blacks of being culturally appropriated for commercial usage. In 2009, the Maori Ngati Toa tribe in North New Zealand officially gained intellectual ownership over the Haka. For Ngati Moa elders this is a very important victory, as the Ka Mate Haka is one of many haka’s and not just a battle cry, it is in the broadest sense used to attain and sustain tribal Mana, a belief that is vital to Maori tradition and spirituality. Mana stands at the foundations of the Polynesian worldview, implying influence, authority and the ability to perform in any given situation through supernatural force, and anyone possessing it to be respected accordingly. But mana has many faces, it could be your aura, your charisma, or the way that you prove your point. Ultimately, in Maori terms, it depends on how well you put that mana to the greater good of your family, your tribe, other people. It means that light will prevail over darkness, because such are the laws of the universe.

In 2016, Maori have gone global with two rousing haka in their support for indigenous people protesting the multibillion-dollar oil pipeline at Standing Rock in the US. A viral video of about 60 people performing the Ka Panapana and Ruaumoko was viewed nearly one million times, shared 24,000 times and received nearly 8000 comments from around the world. The solidarity expressed through dance and display of pride, has sent a powerful message to Sioux people in their battle to preserve clean drinking water.